Musa Ibn Maimon, a Jewish philosopher, physician, and religious scholar who lived from 1135 to 1204, wrote “The Guide of the Wanderers” or “Dilalat al-Haareen,” which has recently been translated and explicated in four volumes by the author Farzaneh and the multilingual translator Shirindokht Dakhiyan. It was released by the Iranian Harambam Foundation’s publications, which are connected to the Federation of Iranian-American Jews in Los Angeles. Ibn Maimon originally wrote this book in Arabic and Hebrew script, and the translator’s first translation from English into Persian was of the full work.

Maimon Ibn

One of the final philosophers of the “Golden Age” of Muslim rule in Andalusia and the Maghreb, Ibn Maimon al-Qurtubi tended to bring Aristotle’s philosophy closer to religion after Ibn Rushd, Farabi, and Ibn Sina. His thought served as a springboard for Spinoza and other Enlightenment philosophers as they ascended to the pinnacle of rationalism, and it assisted Aquinas in bringing scholastic discipline to Catholic jurisprudence. Ibn Maimon, a religious jurist, however, classified the Talmud’s oral narrative, which was written between the fourth and sixth centuries AD in irregular Babylon and Palestine, in light of Aristotelian wisdom, and in addition to the 613 “laws” that He compiled, nearly 15,000 Talmudic “laws” derived from the Torah (which defined the life of a Jewish person from the roof to the evening and from the cradle to the grave). That is, the same jurisprudence that gave rise to the “theocracy” system and the norms for stoning, apostasy, enslavement, and sexism found in Muslim jurists’ theoretical and practical treatises. While it is true that Ibn Maimon rejected astrology, questioned the afterlife, and emphasised wisdom in addition to revelation, he was never able or willing to advance beyond the Torah and Talmud as a religious authority. Because Spinoza, a rationalist, concluded that the Torah’s theocratic system indisputable results in the political castration of the mind in his “Theological-Political Treatise” of 1670. It is also difficult to refer to Ibn Maimon as a rationalist philosopher if we assume that he was mysteriously aware of the secrets of the “Zohar,” the first book of Jewish Kabbalah mysticism (which was revealed in 1290, 84 years after his death), and that he assigned a supernatural value to the letters of the Hebrew alphabet.

Before Ibn Maimon was born, the fanatical Arab Muslims who established the Murabatun dynasty destroyed the control of the Umayyads in Andalusia, where the Jews had previously enjoyed some measure of religious freedom during their rule and particularly under Abd al-Rahman III. When the fanatical, brutal Muslims destroyed the Marabtun dynasty in Cordoba and created the Islamic emirate of Muhdoun, which required that Jews convert to Islam or perish, Ibn Maimon was only a young child. Ibn Maimon and his family eventually relocated from Cordoba to the Maghreb city of Fez before ending up in Fustat, Egypt. The Sunni Ayyubids had lately taken control of this territory from Fatemin Ismailis. He moved to Egypt and started treating Salah al-Din Ayubi and his family while also taking over as the Jewish community’s spiritual leader.

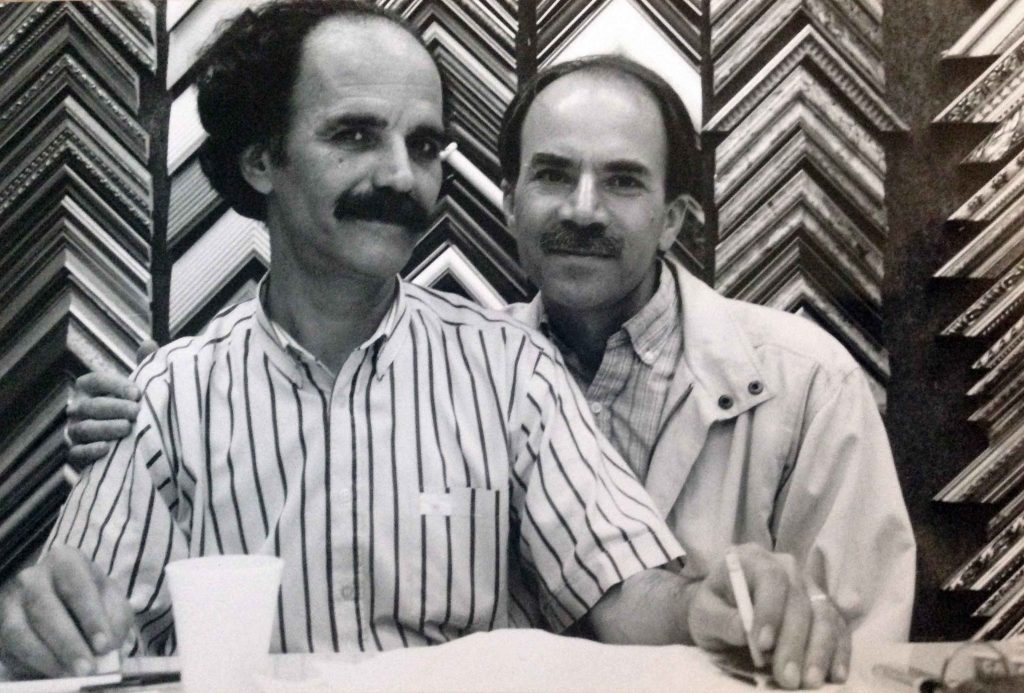

Farah Taheri and Shahrvand’s photograph of Shirindokht Dakhiyan

Ibn Maimon, a Jewish religious figure who upheld the theocratic structure of the Torah, neither desired nor was able to oppose theocracy among Muslims and Christians. Additionally, he did not in any way criticise or negate the anti-human laws of the Torah, such as those against stoning, apostasy, slavery, and sexism, because he believed that the Torah was God’s law and as such was infallibly “timeless” and “unchangeable.” Knew. In the description of Ibn Maimon’s book “The Guide of the Lost,” Shirindukht Dakhiyan takes the form of broadening the scope of the “little renaissance” of the time of Muslim control in Andalusia and emphasising Ibn Maimon’s sense of social sympathy (since he was raising money to free slaves).

On the other hand, he wants to portray Ibn Maimon as a social fighter against pernicious ideas and present him as the inspiration for the Iranian people’s democratic struggle against the clergy. Here, he departs from the framework of an atmospheric truth researcher and transforms into an idealist willing to forgo the scientific method in order to interpret a novel idea in an antiquated text: “In the current era, due to the emergence of cortical readings And the violent religions that have endangered global peace and coexistence and have trapped nations in religious fundamentalist governments, the category of interpretation of the holy texts has received increased attention. Any fresh explanation of “Dilalat al-Haareen,” which in the majority of its sections deals with the interpretation of the holy books, must therefore take into account these sensibilities (Volume 1, page 40)

The Islamic political experience

The struggle that was waged in “Outside Rebellion,” “Goethe’s Nights of Poetry,” and the slogans “Maskan” and “Azadi” had begun in the summer and fall of 1356, but it led to a winding path, and gradually by relying on mullahs, mosques, mourning delegations of the chain of 40s, and the like, the slogan of “Islamic government” predominated. Khomeini did this in the name The democratic and non-religious (secular) demands of the people’s movement should not be overshadowed by “new interpretations of ancient scriptures,” even though they assert peace and democracy, and we should not permit various mysterious religious discourses to take precedence over the obvious and unambiguous “individual freedoms.” Ali Shariati proposed discourses like “Alawite Shia” against “Safawi Shia” and “return to the roots” Sadr Islam in the 1950s despite his mistrust of the clergy, but wasn’t this same desire for “new interpretations of ancient sacred scriptures” what ultimately led to Khomeini’s unwelcome rise to power? Didn’t Ali Mirfitrous use his historically inaccurate readings of a radical Sufi figure from a thousand years ago to create a revolutionary “humanist” and pseudo-Marxist today in his best-selling book “Mansour Hallaj” because he wanted to make heroes out old religious and mystical figures?

The Southern Californian Nozorites

Today, both inside and outside the nation, a variety of religious discourses are put forward, which obstructs our social mental space. For instance, Ali Akbar Jafari, the founder of the ” Zarothushtrian Assembly ” in southern California, has attempted a new interpretation of Zoroaster’s “Gathas” and wants to introduce contemporary liberal and feminist ideas into the historic hymns of Zoroaster, on the one hand, and leave out the portions Avesta, on the other hand. Jafari also founded a religious movement based on respect for the principles of democracy and equality between men and women. The activity of this Neo-Zoroastrian cult has so far only resulted in a few factions being formed between Iranian Zoroastrians and Indian Persians, dimming the discourse on democracy, and instilling anti-Arab sentiment in the minds of Iranians living abroad.

Aren’t ghats lovely and profound hymns? Of course, and for this precise reason, I prefer Ali Akbar Jafari and his friends’ contemporary reading and interpretation of this ancient text to the research conducted on it by Ebrahim Pordawood and other Iranian and foreign Avesta academics. It is found in the work of the second ideological abuse group. One seeks to translate an ancient text from its original language and script into a new one without passing judgement, while the other just seeks to utilise it to further his own political and religious agenda.

Irano-Jewish Americans

I wish the author had restricted his efforts to translating and writing the prologue for Ibn Maimon’s book and left it to the clerics and religious scholars to write “commentary” and “commentary,” which by their very nature demand the worth of judgement. Ikash, the author, had two religious leaders of Iranian Jews living in Los Angeles and New York submit forewords to his book in an effort to gain doctrinal support for his ideological interpretation of “The Guide of the Lost” and to advance rationalism among Iranian Jews. I wished he had published his book on his own, avoiding the exploitation of religious authorities and the religious sentiments of Iranian Jews living in America. It is not necessary for religious leaders and scriptures to advance democratic and rational thought. The mullahs, rabbis, mobads, priests, and qutubs should stay in their prayer spaces, and if they wish to enter the public realm, they should remove their “divine” robes and engage in the political and cultural conflict as regular citizens.